Gramophone

Disembodied Voice

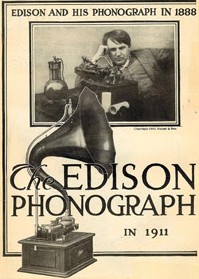

For centuries the desire for music was satisfied by the music hall, the opera house and the parlor piano. Then in 1898 Emile Berliner introduced the gramophone, changing our listening experience forever.

For centuries the desire for music was satisfied by the music hall, the opera house and the parlor piano. Then in 1898 Emile Berliner introduced the gramophone, changing our listening experience forever.

The gramophone and the 78 rpm disc made it possible for music to be experienced personally. But this was criticized at first for corrupting homelife. Listening to music alone was considered odd and even indecent. It was better to do so in company or even at a gramophone concert where it was played to an audience numbering upto a few thousands.1

The gramophone and the 78 rpm disc made it possible for music to be experienced personally. But this was criticized at first for corrupting homelife. Listening to music alone was considered odd and even indecent. It was better to do so in company or even at a gramophone concert where it was played to an audience numbering upto a few thousands.1

Sound recording inserted music into a new socio-economic context where the relationship between musician and listener was mediated by a music “industry” comprising music companies such as Columbia, Odeon and Decca which were the earliest such companies to be formed. This transformed music into a commodity which could be bought, sold and listened to at will.

Some argue that the commodification of music led to its standardization to suit popular taste. This corrupted the artistic process leading to “manufactured” music.

Proponents of recorded music argue on the other hand that the above view is too simplistic. They say that recorded music is a valid art form and that the recording studio is in itself a musical instrument. “Recording music is a complex, multi-stepped process comprised of both art and science, and is defined by an uncomfortable balance between the two.” 2

Recording technologies were agents of social change by bringing the music of marginalized groups to wider audiences – such as Indian tawaifi music – the earliest singers to record in India were courtesans – and African-American music. The earliest records in America and Europe focused on ‘white’ music, such as Western classical music. Recording companies, however, sensed the commercial potential of African-American musicians. The first African-American records were Ory’s Creole Trombone and Society Blues recorded in Los Angeles in 1922. Soon after, recording companies were vying with each other to record artists like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker and others. Jazz had arrived.

By the thirties a sizeable section of the younger white generation welcomed the ‘new’ music. “Conservative whites (and there were a lot of them) were threatened by these social trends. Churches railed against jazz as immoral and issued proclamations against it. Anti-jazz societies were formed. Police cracked down on bars where black musicians performed. And there was even a spiked girdle invented to keep bodies apart while dancing to their tunes3. But it was only a matter of time before jazz was integrated into the American mainstream.

By the thirties a sizeable section of the younger white generation welcomed the ‘new’ music. “Conservative whites (and there were a lot of them) were threatened by these social trends. Churches railed against jazz as immoral and issued proclamations against it. Anti-jazz societies were formed. Police cracked down on bars where black musicians performed. And there was even a spiked girdle invented to keep bodies apart while dancing to their tunes3. But it was only a matter of time before jazz was integrated into the American mainstream.

The production of 78 rpm records started petering out in the 1950s and are now collector’s items. In India from the 1940s to 1960s, several flea markets in major cities were flooded with mountains of records available cheap at throw-away prices.

Out of over half a million Indian 78 rpm records, only few thousand copies have survived and are resting in the music departments of universities but mostly with private collectors. Their collections today are practically the only reference source for many of the recording artists of the gramophone era.

More Photos

https://wiki.brown.edu/confluence/display/mcm1700n/A+Brief+History+of+the+Gramophone

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtrjrrwrPxg

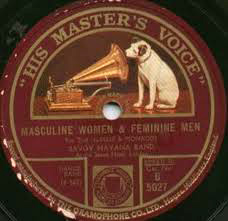

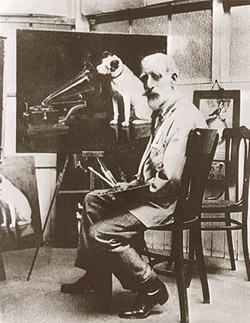

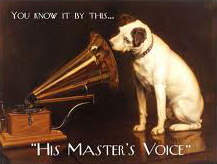

Francois barraud designed the gramophone’s co’s logo –

http://www.designboom.com/history/nipper.html

1 http://www.cph.rcm.ac.uk/MusicRoom/070115Summary.htm

2 http://www.positive-feedback.com/Issue2/RecordedMusic.htm

3A. B. Spelman, Ebony magazine, Revolution in sound, August 1969