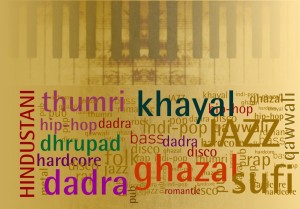

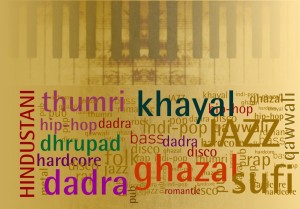

Whenever we talk about Indian classical music, there is a recurring mention of genres like Khayal, Thumri, Dhrupad and Ghazal. And very often people are unaware of the nuances of these terms. So, we’ve put together a little something for you. Part-glossary, part-historical analysis, this article tries to cover some classical genres that have been intrinsic to the Indian Vocal Tradition.

Over the years, Indian music has adapted itself to the cultural and aesthetic demands made by their new patrons. The oldest surviving form of Indian classical music is the Dhrupad, which initially polarized as temple music. It is said that Dhrupad descended from a form known as the prabandha, which was a fixed composition, having a beginning and an end, and set to a raga and tal. One of its most prevalent forms that survive today is the concert form which was represented and made popular by the Dagar Family through the ‘Shiva Stuti’.

Dhrupad composition thematically ranges from the religious and spiritual to royal panegyrics, musicology and romance. However, with the changing audience and listenership, there was need to relate to a wider area of human experience, and responding to the changing times Dhrupad gathered under its rubric, other forms like Dhamar. It appears significant that, in more recent times, Dhrupad and Dhamar have evolved as a pair. In Dhrupad, you might have themes that deal with courtly life or theological themes. But, alongside Dhrupad, you have Dhamar, which deals with secular themes. Even tempo-wise, Dhamar is a very different kind of music making.

Dhrupad composition thematically ranges from the religious and spiritual to royal panegyrics, musicology and romance. However, with the changing audience and listenership, there was need to relate to a wider area of human experience, and responding to the changing times Dhrupad gathered under its rubric, other forms like Dhamar. It appears significant that, in more recent times, Dhrupad and Dhamar have evolved as a pair. In Dhrupad, you might have themes that deal with courtly life or theological themes. But, alongside Dhrupad, you have Dhamar, which deals with secular themes. Even tempo-wise, Dhamar is a very different kind of music making.

By the middle of the 19th century, khayal had all but eclipsed dhrupad as the preferred vocal style for royal courts as well as other performance gatherings of musicians. The term khyal comes from the Urdu word meaning “thought” or “imagination”. By the turn of the 20th century khyal had become the most widely performed classical genre of vocal music in Northern India, supplanting the older austere vocal form called dhrupad. Khayal caught the air of contemporaneity, and incorporated many innovative themes under its rubric. The myriad shades and colors of hallowed and romantic love, the feats of Krishna as an infant, lover and savior, descriptions of the diverse seasons and articulations of intense veneration formed, for the most part, were the subjects of khayal compositions.

The singers took to this rhythmic singing with much gusto. The outcome of this7 lovely aesthetic synthesis and gradual transformation that took place over long periods of time was the khayal. Put simply, the khayal became more fluid and flexible, yet without compromising on its classical ethos or structure.

With the development of Khayal, love became a predominant theme in vocal music, then whether it was Virah (separation) or whether it was Prem (romantic love), the songs were very often addressed to the beloved. The sensuous mood of love is perfectly captured by the Thumri. One of the suggestions of the origin of this term is the word ‘thumkana’, which refers to a sensuous, attractive gait. Thumri was often sung by the courtesans and thus reflected upon their sensuality especially the thumak (a dance movement using the waist), it took on the name Thumri. The theme of human relationships runs strongly, celebrating the unison of lovers and the pain of separation. An important aspect of the thumri is who is being addressed – the ‘Lord’ Krishna, the ‘lover’ Krishna or the ‘confidante’.

As was with many music and dance forms at the time, the thumri and the dance form of kathak were associated with courtesans or tawaifs before they gained currency and status. It is the languor, the lilt, the amorous innuendo that can make listening to a thumri an exciting at the same time a sublime experience – exemplified by Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Saheb singing Prem Jogan Ban kein the Raag Sohini, to a romancing Dilip Kumar Saheb and Madhubala in Mughl-e-Azam!

With the changing form of entertainment, Thumri became a preferred form of vocal expression and a number of renditions in the early phase of recording in India were that of thumri. Most of these recordings were in female voice. Women played a very important role in the development of thumri as well as in the early development of recording industry in India. It was the Women On Record that took on challenge of the changing technology and adapted to it, and thus played a huge role in democratizing music and making it available for a wider audience.

Coming back to our discussion about the vocal genres, we move on to the he period from the 13th to the mid-18th century that brought with it the diverse cultures and thus initiated the process of cultural co-mingling. Music transcended the many boundaries which otherwise existed and incorporated the diversity under its corpus. Many raagas and styles of musical renderings took on Persian, Arabic and Turkish hues and echoed a beautiful syncretism.

In this period, the vocal style which became very popular in the royal courts was the gazal. It invoked the melancholy, love, longing, and metaphysical questions. In the eighteenth-century, it was used by poets, writing in Urdu, a mix of the medieval languages of Northern India, including Persian. Even today, Gazal enjoys phenomenal popularity in Northern India.

Indian classical music has come a long way and in the course of its journey, it has adapted and incorporated a number of singing styles and listening preferences. The long journey of Indian vocal tradition mirrors a spectrum of diverse Indian traditions and cultures. And, even after years of its beginning, Classical music continues to receive prodigious popularity among the music lovers. So, we hope that our brief introductory note on different genres of Indian vocal tradition is useful for some very preliminary understanding. However, it is beyond the scope of an article or even a book to capture the nuances of these different vocal genres of music.